15 things we learnt at ‘Rethink Rubbish’

Lewes Climate Hub’s Rethink Rubbish season in March covered an array of topics from tackling plastic pollution to what happens to our kerbside recycling to how new materials might allow us to ‘design out waste’. Ann Link takes stock of some of the most useful and surprising things we heard.

The Rethink Rubbish season at Lewes Climate Hub looked to tackle the thorny issue of waste: what we throw away or put out for recycling, what happens to it when it’s out of our hands – and how we might completely rethink and reduce what we define as rubbish.

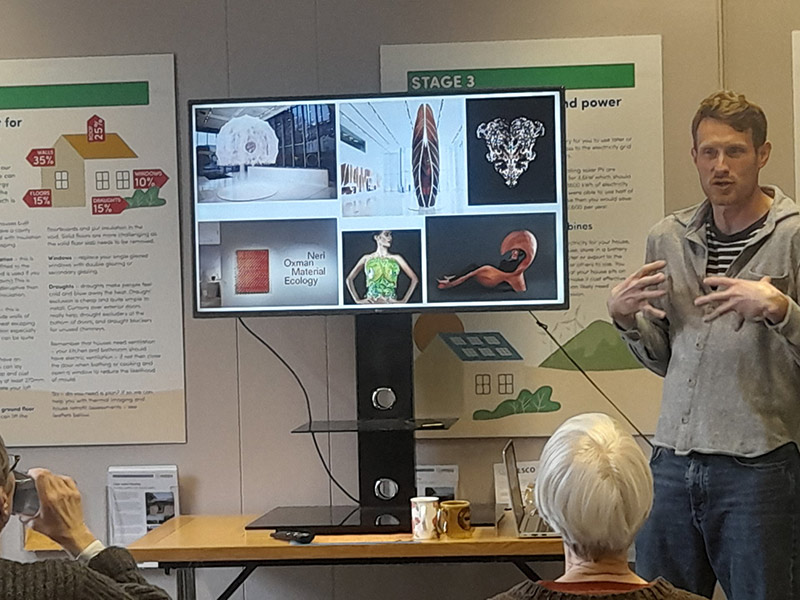

To help explore the subject, we had brilliant talks from Andy Dinsdale of Strandliners, Ewan Topping of The Ocean Cleanup and Dougal Fleming from Clean Growth UK. There was also a fantastic and lively panel discussion about what really happens to our household waste, with Neil Peters from Lewes District Council, Cat Fletcher, founder of Freegle, and Councillor Wendy Maples, who is LDC cabinet member for waste and recycling.

All the speakers addressed ways of avoiding creating waste in the first place, as well as dealing with what is produced by over-consumption and use of materials.

Here are a few of the things we learned

- Strandliners do far more than clear up beaches and rivers. They collect data on what they collect so plastic waste can be reduced at source by understanding which companies are responsible for the plastic that’s being discarded in the first place. And they’re always looking for more volunteers, beach-clean and litter-picking groups to help build up that data.

- The Ocean Cleanup aims to remove 90% of floating ocean plastic by 2040. They work with governments, individuals and corporations to tackle the 1,000 most plastic-polluted rivers in the world. They intercept the waste on a contract for five years. This aims to give countries enough time to establish permanent waste management solutions so hopefully far less plastic pollution ends up in rivers and seas in the first place.

- Lewes District Council is offering a £50 voucher for reusable nappies to new parents. It has partnered with Cheeky Wipes are an independent local company that supply modern, fitting reusable nappies, wipes and more from their factory in Newhaven. See more at https://www.lewes-eastbourne.gov.uk/cheeky-wipes

- Our local Freegle group has over 13,000 members, according to Freegle co-founder Cat Fletcher. You can pass on anything that is legal, and the most unlikely things can find homes with someone able to adapt them, from bubble wrap to a single wellington boot!

- Discarded batteries frequently cause fires in rubbish and are a growing problem, says Neil Peters at Lewes District Council. This is partly because batteries are now built into so many more everyday items, from vapes to even sports shoes. Indeed, any shop that sell batteries or items with batteries must offer to take them back. Make sure no batteries end up in your rubbish.

- Lots of packaging is simply not viable for recycling, e.g. Tetrapaks. From Lewes, for example, empty Tetrapaks have to be taken in lorries to Yorkshire, which has the only UK processing plant for them. Some fibre is recovered, but much of the remainder is incinerated, which might as well happen in Newhaven and avoid the transport.

- You can find a comprehensive list of where to recycle items and materials at https://www.lewes-eastbourne.gov.uk/wasteAtoZ If an item isn’t detailed, you can ask the team and they will tell you whether and where it can be recycled. They will then add these details to the online list.

- Lewes District Council (LDC) is the only authority in East Sussex to collect food waste. It is taken to Whitesmith, where it is processed in an in-vessel composter along with the garden waste from the other districts in the county. This mixture is held at a high temperature (to kill pathogens) for two weeks, and then spread in big rows in the open to finish rotting. The result is given to farmers as soil conditioner, and to charities, and also sold in bags at household waste centres as ProGro. Lewes’ own garden waste, meanwhile, goes to Isfield where it is composted in the open, more slowly than at Whitesmith.

- Vegware (used by many conscientious food businesses) is not easily compostable. It can only be processed in industrial composters. It should not be put in food waste bins.

- Plastic film can be recycled with household waste, except cling film and bubble wrap. Composite materials such as pet food pouches cannot be recycled by LDC: take them back to the supermarket, many of whom will also take plastic film, such as plastic bags.

- LDC already recycles 43% of our household rubbish by weight. It is aiming at 50%. The total waste includes garden waste, dry recycling, food waste and the remainder of general rubbish. When the new wheelie bins for rubbish are introduced, they will be smaller than the recycling bins, in order to encourage to people to recycle more and throw away less.

- Take-back operations can avoid 85% of the emissions of making a new object such as a truck. For example, fork-lift trucks usually last 15 years and are scrapped, even though some major parts are built to last 50 years. Now a company in Derby remanufactures them for an extended life. Dougal Fleming from Brighton University’s Clean Growth UK platform gave other examples and said that opportunities exist for Sussex enterprises to specialise in take-back of items such as spark plugs, that can be renewed instead of recycled or otherwise disposed. Such enterprises are becoming more widespread and a central part of the so-called ‘circular economy’.

- Mycelium (filament root structure of mushrooms) can be trained to feed on specific wastes. BIOHM researches and licences such processes, for example to make an alternative to plasterboard, which is polluting and non-recyclable. These new ‘cradle to cradle’ processes imitate nature, enabling materials to be constantly renewed rather than used once and thrown away.

- Wishcycling is what Cat Fletcher calls the act of putting something into your recycling just because you hope it can be processed. But don’t! Unsuitable items such as wet paper, for example, can spoil all the dry paper in a recycling load so that it has to be incinerated instead of being recycled.

- Finally, when it comes to managing rubbish and plastic pollution, don’t feel guilty but do what you can to tackle it. As Cat Fletcher points out, householders are only responsible for 18% of waste generated in East Sussex. Much of the rest is from building and landscape management, so this is where anyone concerned about the volumes of waste going to landfill or incineration really need to focus their efforts. As for the rest of us, as Cat Fletcher says: Buy less, share more, and enjoy life!

Anything else you’ve learned about waste, recycling or plastic pollution? Send us your suggestions by email